The giants of African literature sprung up during the 1950s when the spirits of revolution and freedom were spreading throughout the continent. The most famous figures to pop up during this time being Chinua Achebe, Cyprian Ekwensi, Amos Tutuola, and a little bit after them was Flora Nwapa. She’s an icon of both world and African literature that needs to be remembered.

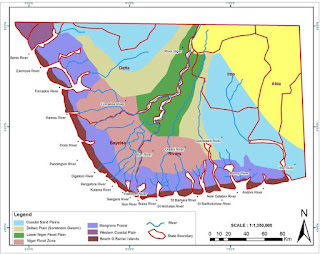

Flora Nwapa was born Florence Nwanzuruahu Nkiru Nwapa on Januray 13, 1931. Her family and childhood were not the ordinary upbringing that an Igbo in Oguta would have had in colonized Nigeria. The Nwapa family line was a powerful and influential one with ties into religion, politics, and commerce. All of these things were integral in her art, career, and life directly or indirectly.

Her parents, Christopher Ljeoma and Martha Nwapa, were prominent figures in the Igbo community and Oguta, Enugu at large. Christopher worked for the United African Company and Martha taught both drama and history. Flora’s uncle, A.C. Nwapa aka Golden Water Boy was the first Nigerian Minister for Commerce and Industries. Her grandparents were huge figures in introducing the Anglican Church to Igbos. Christianity was important to Flora but the Igbo religion was equally as important.

In her schooling, they celebrated and taught about the Igbo culture and religion. Even with the strong Anglican presence in the region, the people made sure that the children knew more than just the imported British culture. In addition to English, Igbo was spoken as well to maintain the pre-colonial practices were encouraged at large.

Martha Nwapa also had a sewing and mending side business. Flora helped her mother. The local women would regale her with the Igbo folklore and mythology. The tales of goddesses fascinated her, in particular the water goddess. This was the initial spark of inspiration. Hearing the folk tales and seeing the lives of local women, these were subjects that weren’t covered in the literature she was exposed to. Since there was not many female African writers at the time, she didn’t make that first step to write yet. She was always an avid reader. Charles Dickens, Jane Austen, and William Thackeray were her favorites.

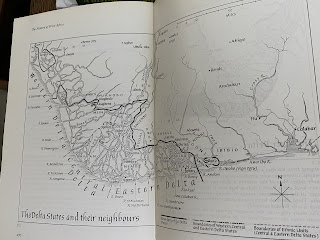

Throughout her childhood, talk of breaking away from Great Britain was abundant. There are the three major ethnic groups in Nigeria - Yoruba, Igbo, and Hausa-Fulani. The Yourba are in the west, Igbo in the east and Hausa-Fulani in the north. A Nigerian nationalistic movement started with the Igbo and Yoruba. The Hausa-Fulani were resistant and held most of the political power among the Nigerians. The independent fervor with the Igbo and Yoruba only intensified during World War 2. The British mostly left Nigeria alone since they could rely on the Hausa-Fulani to maintain colonial way.

Great Britain was gradually withdrawing but was still present. The cultural tensions between the Yoruba, Igbo, and Hausa-Fulani increased. The movement towards decolonization, independence, and modernization reached a fever pitch. Two leaders in particular led the charge to independence, Jaja Wachuku and Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti. Eventually, they came to an agreement for their own nation. On October 1, 1960 Nigeria became independent but more problems cropped up shortly after freedom was attained.

In 1953, Flora started at the University of Ibadan and also served as an education officer for the Ministry of Education. After a BA from Ibadan, she continued her education at the University of Edinburgh pursuing Education. She became an English teacher in Enugu after Edinburgh. It was around this time that Efuru was started. There are several stories from different family and friends of how and when it started but I will stick with Flora's version. She was driving to her brother's house when the idea first popped up. Once she got to her brother's place, started writing down everything before she forgot. This is also her brother's version of the story.

Contrary to popular belief, Nwapa was not the first African or Nigerian woman to be published. She was the first African and Nigerian female novelist to be published in English and internationally. Prior to her, there were female poets and children’s authors who were had already been published internationally and nationally. She had a rival of sorts in Mabel Segun, a poet and children’s author. Segun was internationally published before Nwapa, Germany to be specific. The difference for Flora was that she had the support of one of the biggest names in literature, Chinua Achebe. He is integral to Efuru getting published to begin with. When Achebe got a hold of it, he sent it to Heinemann Publishing in London. It was printed and shipped worldwide. History was still made. (Sidenote: She and Chinua never saw each other again after he needed a wheelchair.)

|

| Mabel Segun, at 90 |

The critical response was lackluster, but it was a success regardless. Western critics perceived it as weak writing with inauthentic story. One of these is an argument that I can understand and the other is nonsense. You can’t ignore the potential of built-in racism with the new wave of African literature and Western response to it. Efuru broke and expanded what was expected in the emerging African literature movement. The women in the previous works, in particular novels by Cyprian Ekwensi, lacked much life outside of something to hinder or support the lead male characters. Achebe was also guilty of this to a lesser degree. Flora populated Efuru and her later novels with complex and complicated women. Even though her work is undeniably Igbo, it’s still universal.

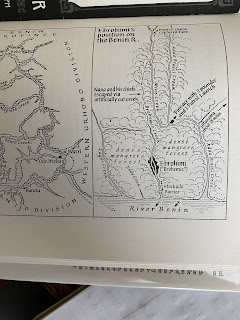

At the time of Efuru’s release, she was working at the University of Lagos. This ended when the Biafra war broke out. The tensions between the the three large ethnic groups (Yoruba, Igbo, and Hausa-Fulani) only grew since the birth of an independent Nigeria. Abubakar Tafama Balewa, the first prime minister was Hausa. He was assassinated in 1966 during the first of 2 military coups that year. This was January, 1966. There was an anti-Igbo pogrom starting in May, about 100,000 died. It continued until October. Several Igbo fled to the west and north. The Igbos were treated with disdain and distrust, especially the North. The second military coup was July the same year. Igbos were still being harassed and targeted in parts the other regions particularly, Hausa-Fulani. An estimated 1 million Igbos returned to their home state. 1967, Emeka Ojuku, the Igbo military governor declared that his region was independent from the rest of Nigeria. The new president, Yakubu Gowon, sent in the military and cut off supply lines of food and resources. 2 million civilians starved to death, this took up majority of the death toll. 3 years later, the Igbos were forced to concede. Things have not reached this boiling point again but there is still tensions between the Igbo and rest of the nation.

|

| Google celebrating what would have been her 86th birthday on January 13, 2017 |

Nwapa returned to Oguta to help out where she could. She saw how the women were running things while the men fought off the Nigerian army and navy. The women would sneak into Yoruba villages in disguise to get food and resources. This and other things she saw on the home front inspired her 2nd novel, Idu. At this time, she also married Gogo Nwakuche. They had 3 children (all of them lawyers now). Gogo was an industrialist but she was the breadwinner. This marriage surprised many. Gogo married up but her family and friends were always confounded by her choice of a husband. Already independent minded, the experience of the Biafra War kickstarted her into a political career, along with boosting her writing one.

Following the war, there were 350,000 orphans that needed care and a home. The Nigerian government shipped them off to several other African nations. Nwapa, as a person and the Minister for Health and Social Welfare in the Igbo region, did not like that approach. She organized a program to retrieve the shipped off orphans, track down their family remained, and reunited broken families as much as they possibly could. This was largely successful in bringing families back together from the war. She was then the Minister for Land, Survey, and Urban Development. During her time in office, she opened up Oguta Lake for the public. Oguta’s economy boomed with the influx of visitors. Her political career was voluntarily over in 1976, but in that time she garnered a lot of respect in that brief 6 years. She was the first women to hold between of those offices.

Oguta gave her the chieftaincy title Ogbuefi (Killer of the Cow) of Oguta. This title was traditionally saved for men. Flora was the first (or one of the first) woman to hold this title. Also President Shehu Shagari bestowed the OON, Officer of the Order of the Niger, onto her in 1983. In the twilight of her career, she was a regular speaker and teacher at universities around the world. When she traveled, her kids would come along with her if possible. By all accounts, she was a warm and lovely person. Flora was also a big fan of Fela Kuti (son of Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti) and Tony Allen. She reached levels that weren't given to women and didn't change who she was.

She achieved many things throughout her political career. The achievements above are the most prominent but she did more. In her literature, women are central. The stories, plight, and triumphs of African women were always central. Efuru is the mission statement. It’s centered on Efuru, a successful trader, and her life. She’s independent and goes after what she wants despite the societal barriers. Politically, she always pushed women's issues and ways to help and empower women every chance she could. Perhaps, the most baffling aspect of this is her take on feminism. She did not call herself a feminist, instead she preferred the term, womanist. This does not change the outlook or impact of her career. The work speaks for itself.

In 1976, she went full-time as a writer. By this point, she had enough clout and influence to create her own publishing company. This was Tana Press. With this, she had the power to put out her work at the pace she wanted and created a space for other women in the writing world. Flora forged a path for herself and left it open for others to follow. During her lifetime, she was a towering international figure but was seemingly forgotten as soon as she died.

Flora Nwapa died on October 16, 1993 in Nigeria Teaching Hospital in Enugu from pneumonia. At the time of her death, she was working her final novel, The Lake Goddess. This was later published in 1995.

Bibliography

Novels

-Efuru, 1966, Heinenmann

-Idu, 1970, Heinenmann

-Never Again, 1975, Tana Press

-One Is Enough, 1981, Tana Press

-Women Are Different, 1986, Tana Press

-The Lake Goddess, 1995, Africa World Press

Short

Fiction and Poetry

-This Is Lagos and Other Stories, 1971,

Nwamife

-Wives At War and Other Stories, 1980,

Nwamife

-Cassava Song and Rice Song, 1986, Tana Press

Children’s

Books

-Emeka, Driver’s Guard, 1972, University

of London Press

-Mammywater, 1979, Tana Press

-The Adventures of Deke, 1980, Tana Press

-The Miracle Kittens, 1980, Tana Press

-Journey To Space, 1980, Tana Press

References

https://www.sahistory.org.za/archive/biography-flora-nwapa-emily-coolidge

https://scholarblogs.emory.edu/postcolonialstudies/2014/06/11/nwapa-flora/

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3ZT5_YeTPos, House of Nwapa documentary by Onyeka Nwelue

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7JCvIvb8PpY, Biafran War Explained

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=f9cSA1gLizE, Nigeria’s Civil War Explained - BBC News

http://authorscalendar.info/nwapa.htm