|

| Nana Olomu, last Gofine of the Itsekiri |

When it comes to Nigerian history, the major peoples are the Yoruba, Igbo, and Hausa. They are the three largest ethnic groups out of the 300 or so different peoples living in Nigeria (that means roughly 300 different languages and everything that goes along with that). Historically, the main 3 are important but that’s only the tip of iceberg in exploring the Nigeria's cultural history (a brief aside…Nigeria was never a unified empire. That Nigerian prince scam is playing off of ignorance and casual racism. Back to the topic at hand).

One of the major peoples that should be more known is the Itsekiri of the Warri Kingdom or Iwere Kingdom. There are several names but refer to the same people. Here, I’ll use Itsekiri since that was how I first learned about them. They are not only monumentally important in Nigerian history but also have a rich and complicated history. They’re central in one of the key events that led to the colonization of what became modern Nigeria, the Ebrohimi Expedition.

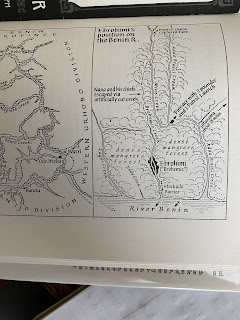

First, where are the Itsekiri? They were one of the many states in the Niger River Delta. The other Delta states were the Nembe (who adopted the Itsekiri god of War, Ogidiga, as their own state god), Okrika, Ogoni, Ikwere, Odual, Ogdin, Apoi, Bassom, Kalabari, Urhobo, and Arogbo. All of these were connected by a complex intertwined system of rivers on the Atlantic coast. The region is swampy, wet, and humid so imagine the Everglades or Atchafalaya Basin. Mangrove trees, freshwater rain forests, and low level rain forests line the waterways. The Delta is a complex ecosystem with distinct and varied fauna and regions. The Itsekiri moved into the northern saltwater area, which was integral to them dominating the region.

To get around, you traveled via canoe. Bigger boats were not functional throughout the delta. The canoe is life blood of survival. It was your way of get around and to defend yourself. Naturally, these would turn into war canoes. These were specialized canoes with cannons that needed a lot of manpower as well. Their accuracy was not the best, by many accounts. They were effective but were not used regularly. In general these were saved for “wars.” Not the full-scale, months long ordeals that their non-Delta neighbors raged. The Delta “wars” were infrequent but common enough that the major states had several at hand for just-in-case.

When compared to the other nearby kingdoms and empires to the North (Oyo, Benin), the Itsekiri are notably different from the rest. They were not a military power. There was never an organized army or navy. They specialized in trade. The “wars” that broke out were always between traders either from the same state or a nearby state. These lasted a few days at the most and causalities were typically low. Each state had there own specialties. The Itsekiri were kings of salt, vegetation salt to be specified. There are 3 types of salt - vegetation salt, sea salt, and mineral salt. Itsekiri harvested leaves from white mangroves. The process from leaf to salt was a 4-step method - 1) Burn the leaves, 2) Soak the ashes, 3) Wash the ashes, and 4) Evaporate the ashes and collect the salt residue leftover. According to legend, salt-producing predated fishing. It was an integral part of their culture and trade. Overtime, they were forced into expanding into more markets than fish and salt. Then the Portuguese arrived. The slave trade was already active but Portuguese were less interested in salt than slaves. Eventually, the salt trade died down and palm oil became the dominant trade. Also, ivory and timber but these were a lesser industry compared to palm oil.

|

| Itsekiri Emblem |

Before diving fully into the Europeans, I need to get to the Delta societies. Even though there are several different states in the region, there are several similarities and cultural crossover. First the important aspect the House system, this is a common factor across the Delta. The house broke down into four different levels - Chief, Sub Chief, Freeman, and Slave. The focus will obviously be the Itsekiri but this carried over throughout the Delta. As was mentioned above this area was an economic powerhouse not military, everyone was a merchant or trader. Especially the Itsekiri, to have any social status at all you had to have a product, trade route, wealth, and connections. Even the slaves, were traders too. Slavery here had a different context. It didn’t mean property, it was a social rank with the potential to move up but not be royalty. The House was a trade organization. The ranks were not set in stone, a slave could become chief of a house potentially. These chiefs were the advisory council for the king. However, there was still a royal family. Rivalry between the houses was always a threat. For the Itsekiri, the royal family had a house and were traders with their own House as well.

The House system was integral to the Delta states (rumored to have come from the Ijo people but it’s still unclear). These held political and financial power in each city in the region. There was a royal family for the Itsekiri but they were also traders and had to actively maintain their status as much as everyone else. These were states with multiple cities within them but they functioned closer to city-states than a totally unified kingdom. They had their own sub cultures and customs. Assimilation and mono-culture was fundamental in taking new slaves, which was a class (still people under the law but social mobility was possible and greatly encouraged). The success of a House was determined by the number of slaves, war canoes, trade partners, and how many members of that House have moved up a class or two. If a House, had several slaves that retained their native culture and did not move up socially that House was seen as weak and would their status in their city. This could be result in them leaving the royal council and a line to the king.

|

| Mangrove Roots |

To maintain a House, you needed to have money, slaves, and a growing business. Slaves were typically foreign and brought into Houses to handle the labor. Each city had societal groups to encourage and even force assimilation into their culture. They were ceremonially shaved, given a new name, and given a new “mother.” This was the first step in building them up and the House. Next, the slaves were taken over to the Sekiapu. This was a societal group that known the drum language, all the dances, customs, and everything else that was needed to become a full citizen. Like everything else, the Sekiapu was picked by merit and money not bloodline. Another group that was integral in this routine was the Peri Ogbo. This was a club for veterans of business and the “wars” that had killed or captured people. If a slave resisted too much, they were called in to investigate and/or punish depending on the case. In the Kalabari state, they had the Koronogbo (club of the strong), who would roam the streets checking that the lower classes were properly assimilated. The individual cities (or city-states) were naturally suspicious of outsiders and even a foreign accent could be a sign of a spy from a rival. Without an overwhelming military their was not a strong sense of unity. Inter-House and Exterior conflicts between Houses, cities, and states were common. Bloodlines didn’t give you status but how successful your trade organization made you. The lack of a strong central government and military eventually led to their downfall centuries later. The Houses held political power as well as the village elders. The heads of Houses made up the Ojoye, the Olu’s noble advisory council.

|

| Nana's sons and nephews |

The Itsekiri were not always an independent kingdom but they maintained a sense of independence. They were a part of the Benin Kingdom (or Dahomey). The Benin Kingdom goes back to the 12th century and became one of the major players. Technically, they were under the Benin until the 19th century. Seemingly, they were left alone in the swamps to do what they wished. So, they developed a capitalistic monarchy system and controlled the waterways. The Benin Kingdom among others relied on them and the other states for trade. The Itsekiri broke off, sort of, from Benin in the late 15th century. Settling in the Niger Delta, they had to focus on trade since empire-building and military operations weren't possible in the area. The first Warri ruler, the Olu, was the Benin Empire’s Prince Ginuwa. He was forced out of the Benin Empire after ordering the deaths of “ungrateful” people who were too critical of his father’s, Oba Olua, kindness and perceived lack of strength. This is oral tradition and legend so who knows how accurate the story but it’s a good story. He left with 70 sons of Benin chiefs in 1473 to settle in the riverine part of the empire. Starting around 1460, Itsekiri refugees started appearing in the neighboring state, Nembe. By 1480, the Warri Kingdom was established and Ginuwa ruled for 30 years. The Itsekiri don’t consider themselves Benin but the royal family and nobles are Benin. Initially, their background was a mix of Yoruba, Benin, and Ijo peoples. Eventually, morphing into the Itsekiri.

Europeans eventually showed up and the Portuguese were first. They were impressed and started to trade firearms for slaves and salt. This only boosted the already strong commerce. Some used guns for defense but the general consensus was firearms for trade. Besides weapons, the Europeans also brought religion. Roman Catholicism wasn’t frowned upon but wasn’t that common. They still actively practiced their own religious practices. By the 1800s however, Roman Catholicism was yet another transgression by the Europeans and repressed more.

At the start of the 1800s, the Itsekiri had maintained such strict control of their region that the Benin Kingdom no longer had any strong influence or presence. There was no civil war or formal separation process. The slave trade was still in full effect but not for long. When the slave trade with the British faded and the switch to Palm Oil followed suite. This still required slaves but the British seemingly didn’t bother to learn the Itsekiri definition of slavery or willingly ignored it. They needed more slaves and got more slaves. The British were not happy and would later be used as a reason to interfere by the British. The Itsekiri royal family, that had ruled since 1480, were gradually losing power.

A major river for trade that also bordered their capital Ode Itsekiri, the Forcados, had been taken by a neighboring state so they had to switch to the Benin River. With this shift, several successful Houses founded 3 new towns. These were Jakpa, Batere, and Ebrohimi. Ebrohimi was a major trade center and in the best position defensively. It was founded by Olomu, the father of the future Nana Olomu. That will became important in a little bit. The royal family’s attempts at maintaining economic presence and power failed. After losing their economic place, they lost favor with the nobles and other powerful Houses. In 1848, there was no royal family in power, Akengbuwa I, stepped down. His sons, Omateye and Ejo, died afterward.

The Interregnum period lasted from 1848 to 1936. The government shifted into the Age of the New Man. The nobles still held power but they were not necessarily in control. There was an election for an executive officer, the Gofine aka Governor of the River. There were only 4 governors before getting conquered - Idiare (Ologbotsere Family), Tsanomi (Royal Family), Olomu (Ologbotsere), and Nana Olomu (Ologbotsere Family). The Ologbotsere effectively replaced the royal family, by being both the most feared and respected House in the state. The former royals, Numa and his son, Dogho, were jealous of the Ologbotsere and specifically, Nana Olomu. They were not alone, The British equally didn’t like Nana and how much he had. He was a stronger and more successful leader than his father. This jealousy led to the fall of Nana Olomu and in turn the Itsekiri.

References

West African Resistance, 1971, 1972. Ikime, Obaro. 205 - 232.

History of West Africa, 1971, 1972. Crowder, Micheal. Ajayi, J.F. Ade. Alagoa, E.J. 269-274, 280-283, 293-294, 302-303.

A Thousand Years of West African History. Ajayi, J.F. Ade. Espie, Ian. Akinjogbin, I.A.. 300-308

History of Nigeria, 1983, 1984. Isichei, Elizabeth. 53.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kingdom_of_Warri#Kings_of_Warri_Kingdom,_1480_to_present

https://www.vanguardngr.com/2016/06/1894-ebrohimi-expedition-itsekiri-leaders-eulogise-nana-olomu/

https://collections.rmg.co.uk/collections/objects/556.html

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Benin_Expedition_of_1897

https://face2faceafrica.com/article/nana-olomu-nigerias-19th-century-millionaire-who-made-slavery-a-difficult-trade-for-the-british

https://kwekudee-tripdownmemorylane.blogspot.com/2014/04/nana-olomu-great-nigerian-millionaire.html

http://www.rogerblench.info/Language/Niger-Congo/Ijoid/General/Izon%20plant%20names.pdf

https://www.oluofwarri.org/itsekiri-history/

No comments:

Post a Comment